- Serving The Fraser Valley & Lower Mainland

- Gas – LGA0103126

- Refrigeration – LBP0001017

- Boiler – LBP0204397

24hr Emergency Service

Click to Call Dispatch

Click to Call Dispatch

Commercial facility managers across Chilliwack, Abbotsford, and the wider Fraser Valley are under increasing pressure to control operating costs without compromising building performance. Energy spending is often one of the largest line items in a commercial budget, and aging HVAC systems are a frequent, but sometimes overlooked, contributor to rising utility bills.

Many commercial systems continue operating well past their intended service life. While this may appear cost-effective in the short term, older equipment often consumes significantly more energy than modern systems, delivers inconsistent comfort, and creates hidden costs that accumulate quietly over time. Understanding how aging HVAC systems affect energy usage is a critical step in making informed decisions about maintenance, upgrades, and long-term planning.

This article explains how older commercial HVAC systems drive up energy costs, the warning signs facility managers should watch for, and how proactive planning can reduce energy waste while extending system reliability.

Quick check

If your building’s utility costs are trending up year over year and occupancy hasn’t changed, HVAC efficiency should be on the short list for review.

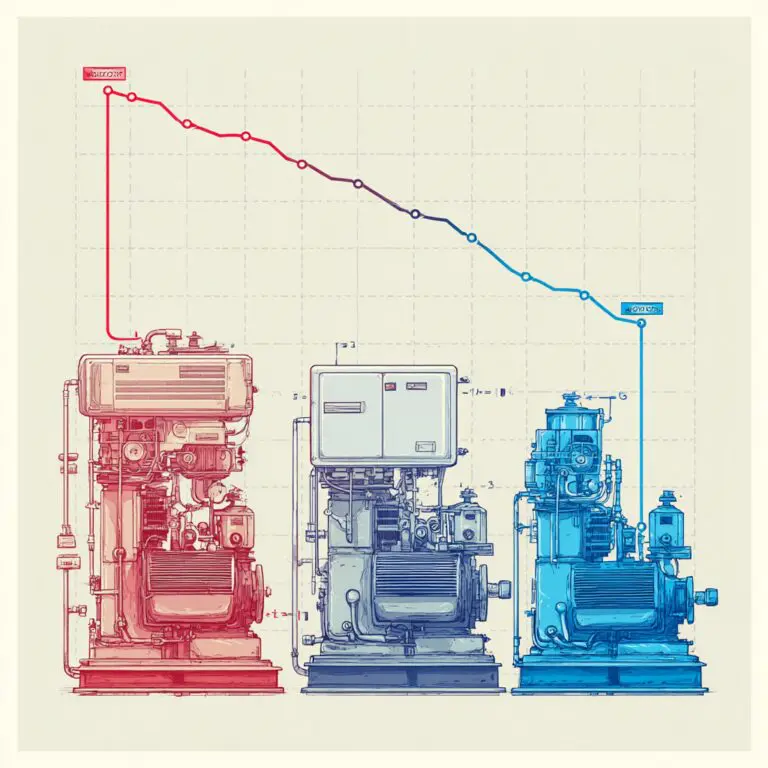

HVAC equipment is engineered with a defined operational lifespan. Even with proper maintenance, components naturally degrade through years of thermal cycling, vibration, and environmental exposure. As systems age, efficiency losses are gradual, making them difficult to notice until energy costs have already increased.

Mechanical wear is one of the primary factors. Motors, bearings, belts, and compressors experience friction and fatigue over time. These components must work harder to deliver the same output they once provided with less effort. As resistance increases, so does electrical consumption.

Control systems also play a major role. Many older commercial HVAC units rely on outdated control logic, pneumatic controls, or first-generation digital systems. These controls lack the precision of modern building automation systems, leading to longer run times, poor zoning control, and unnecessary heating or cooling during unoccupied hours.

Airflow degradation further compounds efficiency loss. Ductwork can accumulate dust, debris, and microbial growth. Dampers may seize or lose calibration. Fans may become unbalanced. These issues reduce air movement, forcing equipment to run longer cycles to meet temperature demands.

Together, these factors create a system that still functions, but at a steadily increasing energy cost.

Older commercial HVAC systems were designed under different energy standards than those in place today. Even a well-maintained system installed 15 to 20 years ago often falls far short of current efficiency benchmarks.

Common energy leak

Fixed-speed fans and compressors can waste the most energy during mild weather, because the system can’t adjust output when demand is low.

One challenge with aging HVAC systems is that energy waste often occurs quietly. Unlike a complete system failure, efficiency losses do not usually trigger alarms or urgent service calls. Instead, they appear as gradual increases in monthly utility bills.

Facility managers may notice higher energy usage during shoulder seasons, when heating or cooling demand should be lower. Older systems struggle to modulate output efficiently during mild weather, leading to unnecessary runtime.

Another common issue is simultaneous heating and cooling in different zones. Outdated zoning controls and worn dampers can cause one area of a building to receive cooling while another is heated, dramatically increasing energy consumption without improving comfort.

Short cycling is also more prevalent in aging equipment. As sensors drift out of calibration and components wear, systems may start and stop more frequently. Each startup cycle draws a high electrical load, increasing overall energy use and accelerating component wear.

Because these issues develop slowly, they are often normalized as part of operating an older building, rather than recognized as correctable inefficiencies.

As HVAC systems age, maintenance requirements increase. While regular service is essential, there is a point at which maintenance alone can no longer compensate for declining efficiency.

Worn components require more frequent adjustments and repairs to maintain performance. Belts must be tightened, motors serviced, and controls recalibrated more often. Each intervention may restore partial functionality, but it rarely returns the system to its original efficiency.

In some cases, maintenance practices unintentionally increase energy use. For example, oversized replacement motors or non-original components may not match system design specifications, leading to inefficiencies. Temporary fixes applied during emergency repairs can also compromise long-term performance.

There is also a labour cost factor. Increased service calls mean more downtime, higher service expenses, and greater disruption to building operations. When combined with elevated energy consumption, these costs often exceed the investment required for strategic upgrades.

Budget tip

Track the total cost to operate, not just repair invoices. A month of higher runtime during peak season can erase the savings of postponing a planned upgrade.

Facility managers do not need to rely solely on equipment age to assess efficiency risk. Several operational indicators suggest that an HVAC system may be consuming more energy than necessary.

The effect of aging HVAC systems on energy costs varies by building type, but the underlying principles remain consistent.

Office buildings often experience increased energy use due to poor zoning control and extended runtimes. As layouts change over time, older systems struggle to adapt, leading to over-conditioning in low-use areas.

Retail spaces face challenges related to fluctuating occupancy and heat loads from lighting and equipment. Older HVAC systems lack the responsiveness needed to adjust efficiently, resulting in wasted energy during off-peak hours.

Industrial and light manufacturing facilities may incur significant energy penalties due to inefficient ventilation and make-up air systems. Aging equipment often fails to recover heat effectively, increasing heating costs during colder months.

Strata and multi-tenant commercial buildings face additional complexity, as comfort complaints and inconsistent performance can lead to manual overrides that further increase energy consumption.

Reducing energy consumption is not only about lowering monthly expenses. Energy efficiency directly affects system longevity, reliability, and compliance with evolving standards.

Inefficient systems operate under higher mechanical stress, increasing the likelihood of breakdowns during peak demand periods. Emergency repairs often occur at premium rates and may involve temporary solutions that further reduce efficiency.

Energy performance is also increasingly tied to building valuation and tenant expectations. Commercial tenants are more aware of operating costs and environmental performance. Buildings with outdated HVAC systems may face leasing challenges or pressure to invest in capital improvements.

In some jurisdictions, energy reporting and efficiency requirements are becoming more stringent. Proactively addressing HVAC efficiency can help building owners prepare for future regulatory changes.

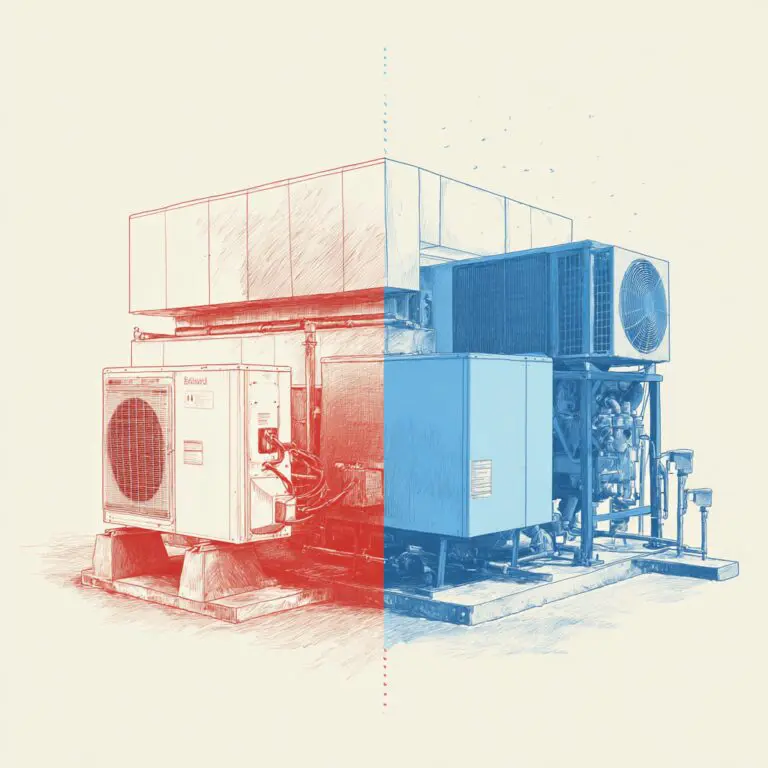

Addressing energy waste from aging HVAC systems does not always require full replacement. A structured assessment can identify which components are driving inefficiency and where targeted upgrades deliver the greatest return.

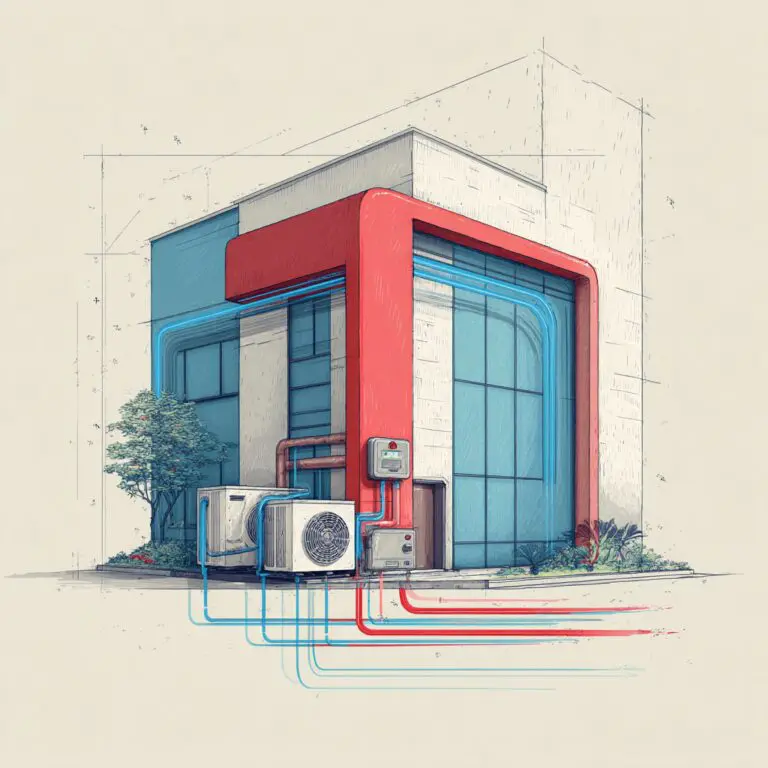

Control system modernization is often one of the most effective steps. Updating thermostats, zoning controls, and scheduling logic can significantly reduce runtime without altering major mechanical components.

Variable-speed retrofits for fans and pumps can improve part-load efficiency, especially in buildings with variable occupancy. These upgrades allow systems to better match output to actual demand.

In some cases, partial equipment replacement, such as upgrading rooftop units or replacing inefficient boilers, provides a balance between capital investment and energy savings.

The key is aligning upgrades with building use, system condition, and long-term operational goals.

Planning note

If replacement isn’t on the table this year, control upgrades and scheduling improvements are often the fastest way to reduce runtime without major disruption.

Effective energy management requires looking beyond immediate repairs. Facility managers benefit from developing a long-term HVAC strategy that accounts for system age, energy performance, and future building needs.

This approach includes regular performance reviews, trend analysis of energy data, and coordination between maintenance planning and capital budgeting. By understanding how HVAC systems contribute to energy costs over time, decision-makers can prioritize investments that reduce risk and improve predictability.

In the Fraser Valley’s variable climate, systems must efficiently handle both heating and cooling demands. Planning ahead reduces the likelihood of reactive decisions made during peak seasons, when options are limited, and costs are higher.

Aging HVAC systems rarely fail all at once. Instead, they quietly consume more energy, increase operating costs, and place greater strain on maintenance resources. For commercial facility managers, recognizing these patterns is essential to maintaining control over energy budgets and building performance.

By understanding how older systems drive up energy costs, and by taking a strategic approach to assessments and upgrades, commercial facilities can reduce waste, improve reliability, and support long-term operational stability.

Most commercial HVAC systems are designed for a service life of 15–25 years. Efficiency often declines well before the end of this range, especially without consistent maintenance.

Maintenance is essential, but it cannot fully restore original efficiency once components and controls have aged beyond certain limits.

An energy and performance assessment helps identify inefficiencies and determine whether maintenance, upgrades, or replacement offers the best value.

No. Control upgrades, variable-speed retrofits, and targeted component replacements can significantly improve efficiency without full replacement.

Aging systems struggle with part-load efficiency and modulation, resulting in longer runtimes and higher energy use during the shoulder seasons.